Hacky Hackin Again: Pennapps XV

Our team wanted to incorporate machine learning and neural networks into our project for our own education. We identified a need for lightweight symmetric key exchange in the ever growing Internet of Things (IoT).

Introduction

This blog post will mostly be entirely self contained, but I do, on occasion, make a call back or two to my first post. So if your feeling pumped about Hackathons you can check that one out here First Hackathon: Pennapps XIV.

In an attempt to capture lightning in a bottle, our team of physicists set out to reign in prizes and free swag left and right. But as you can imagine recreating the magic of my first Hackathon was not so straight forward. For one, arguably our biggest hurdle happened at the very beginning. Which had to do with this small matter of not having come up with hack to work on (suspense grows).

The Competition

This year our team was composed of reigning 3rd place finishers Sebastian, Rob and I along with hackathon newcomer and fellow physicist, Arjun. So I actually had come into the event with a few potential ideas that we could work on. One was what would have basically been an accelerometer+Arduino based device that you could attach to you washer/dryer with the idea being that you could monitor the cycle at some coarse grain level based on some signal processing of the accelerometer data. Which I thought would have been a pretty interesting dive into some data driven analysis. This came from me having to use ancient washing machines in the basements of apartment buildings while finding myself living in the 3rd/4th floor (with no elevator). However not everyone on the team was super pumped about my dumb-to-smart washing machine idea ☹️ . But I'm not salty about this at all. And also to be fair finding a washer/dryer which we could use to collect data nearby the event venue was not really straight forward on such short notice. We luckily all did end up converging on a set of ideas we would like to work with just out of our own interest. These ideas being in the "whats-so-hot-right-now" machine learning/neural net realm. So that was a good step forward. We were then trying to fit these ideas into doing something pertaining to a 'side' competition, i.e. a more focused challenge put on by one of the Hackathon's sponsor companies, often having to use their API and some pseudo-data they provide (things like "Best Finance Hack" sponsored by Capitol One). We did this partially for selfish reasons, if our hack qualifies for multiple categories/competitions we increase the probability getting cool prizes. And partially just because we thought it would help us come up with an idea. Ultimately these challenges were just too narrowly defined and we were pretty stubborn about only working on something were weren't all genuinely interested in. So the brainstorming continued, taking up our entire first evening of the hackathon, which would definitely feed into a time crunch later. With little to show for the first day of the competition we all headed home that evening hoping that inspiration would strike before the morning.

Luckily inspiration struck our boy Arjun, who came in hot the next morning with a banger of an idea. I can't speak for everyone but I immediately thought it was awesome. And we pretty quickly decided to go all in on this hack.

Here's the pitch:

Embedded devices in household or everyday items do not have much processing power or memory; nevertheless, there is a great need to secure these devices from attackers. State-of-the-art exchange schemes such as Diffie-Hellman asymmetric exchange are arithmetically expensive, a fact that prohibits their implementation on constrained-memory systems that sometimes use integer widths as small as 8 bits. This observation led us to the idea of Tree Parity Machine symmetric key exchange, an idea pioneered by physicists in the early 2000's (paper here), and we tested their feasibility on an Arduino system.

And thus came the hack "Cryptoino", the portmanteau of Cryptography and Arduino and not the fermionic superpartner to the Crypto boson (dumb particle physics joke pls keep reading im sry).

The Theory

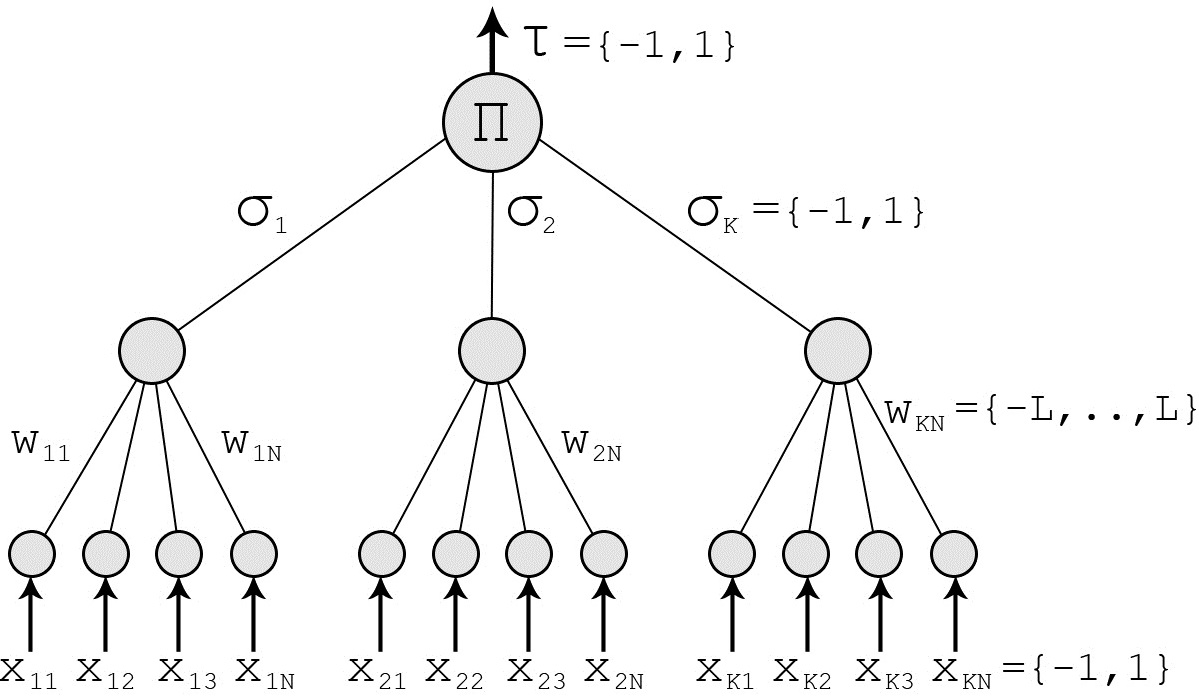

For those who don't like to have a cryptography paper thrust upon them as required reading in the middle of some random blog post I'll try to distill the main points here. Using the neural net diagram below we will walk through what Kanto and Kinser proved in their paper.

For starters the thing in the figure on the right is called a "Tree Parity Machine" (TPM), which is a special type of multi-layered feedforward neural network. In this scheme we have two TPMs of identical structure, tree and tree . The same set of random input vectors of size are fed into each TPM. Then different sets of random weight vectors of size are applied on each TPM. The vectors can take on the following values:

The input values are then weighted according to the Hebbian rule:

I'll spend a little more time here since this is essentially the main logical crux of the entire process. So this Hebbian rule, or Hebbian learning, is something that comes out of neuroscientific theory and is often summarized as "cells that fire together wire together." So a Hebbian rule is a rule that increases (updates) weights (influence) of the network if the neurons of the network are activating together. The sign of the inner product of the weight vector and input vector is then taken after the weights have been updated.

The product of these sigmas is taken resulting in a final output values and , which can take on the numerical value of +1 or -1.

The training, and therefore synchronization, are achieved by comparing the outputs between the two trees, only updating the weights of both trees if the outputs are not the same. Random input vectors are continually generated and input into the TPMs and weights updated (or not) according to the scheme that was laid out. The beautiful thing that happens next is that the weights themselves, in each tree, will synchronize. For the actual proof you will have to check out the paper. But you can believe me, I'm trustworthy, probably.

We now have a secure method of symmetric key exchange.

All the two parties involved have to do is agree upon a neural net topology (within the allowed TPM structure) and follow the prescription laid out previously to be able to securely communicate with each other.

A great visualization that I made during the competition (judges love visuals) is the gif (converted to a .webm) on the right where the neural-net weights are depicted as the colored lines that extend from the input neurons to the inner layer.

The numerical weights are mapped to some color spectrum and so as the weights change the colors change.

The first two networks are the two TPMs (A and B) and the third network is just the difference between the weights of network A and B.

In this way it is easy to see when the networks synchronize as the third network will become a single bright green (green 0.0 in this mapping).

In real time the network synchronizes very quickly but I have slowed it down here just to show the adventure it takes.

Feel free to skip to the end to see it synchronize.

Now that we are done with that bit of book learnin' we can get back to the hack.

The Hack

I was familiar with Arduinos (a popular programmable microcontroller) coming into this Hackathon just because I had purchased one at some point with the idea of doing some fun side projects.

I believe my original weird idea was to make a remote drawing machine/robot thing.

Like if you had one of these devices I could, from my phone, draw a little picture and it would in 'real' time draw my drawing on a piece of paper thousands of miles away via your device.

Things like this exist of course, but I thought, and still think, I could do this easily for super cheap.

And it seemed fun.

That being said I never finished this project, but maybe I'll resurrect it someday, and maybe attach it to a drone or something.

But anyway.

So I after giving the TPM key exchange paper a quick scan and seeing how straight forward the logic should be to write up in some code it seemed simple enough to hook up two of these bad boys together to have a nice proof of concept.

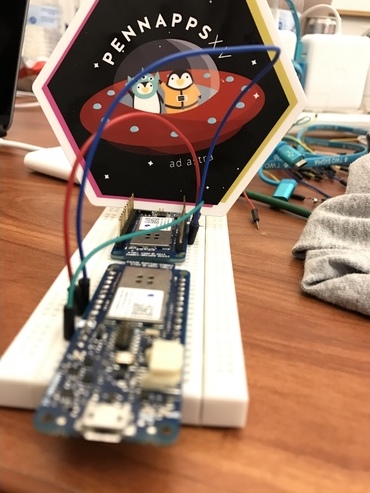

Now the flagship Arduino is the Arduino UNO but it is a little big (relatively) and in the spirit of our hack, bringing lightweight, secure, and fast encryption to small IoT devices, we opted for the smallest of the Arduino line we could source from the hardware library of the competition.

These ended up being two Arduino MKR1000's.

The two Arduino MKR1000's were attached to your standard bread board as you can see in the figure to the right.

Then we needed to make sure we knew what each pin inputs/outputs on the Arduinos were doing, i.e. which were digital, analog, and power.

After this short look up and a bit of a think we hooked up the wires and whbam the hardware part of the hack was essentially done.

On the software side of things we began with a Python implementation of a tree parity machine simulator.

So in this we just wanted to get a proof of concept coded up on our computers so that we had code we new worked before moving to the full implementation on the Arduinos.

The code for this simulator was actually pretty simple so I just pasted the whole script below.

import numpy as np

import sys

def tpmUpdate(x,w,sigma,L,tau):

sigma = (tau*sigma+1)/2 # hacky AND of {-1,1} wrt tau

x = np.transpose(sigma*np.transpose(x)) # don't change hidden nodes with

# output not equal to tau

w += x # Hebbian update rule

w[w < -L] = -L # reflective random walk boundaries

w[w > L] = L

return w

def tpmEval(x,w): # w - weights array

# x - random input matrix

sigma = np.sign(np.sum(x*w,1)) # sum of each row: axis = 1

sigma[sigma == 0] = -1 # conditional replacement

tau = np.prod(sigma) # hidden layer bits combined

return (sigma,tau)

def sync(w1,w2,L): # synchronize two TPMs with initial weights w1, w2

(k,n) = w1.shape

binSet = np.array([-1,1])

i = 0

j = 0

while(not np.array_equal(w1,w2)):

i += 1

x = np.random.choice(binSet,size=(k,n)) # random input matrix x_{ij}

(sigma1,tau1) = tpmEval(x,w1)

(sigma2,tau2) = tpmEval(x,w2)

if(tau1 == tau2):

j += 1

tpmUpdate(x,w1,sigma1,L,tau1)

tpmUpdate(x,w2,sigma2,L,tau2)

return (i,j,w1)

def initialize(L,k,n): # initializes a weight matrix with vals {-L,...,L}

# and dimensions (k,n)

w = np.random.random_integers(-L,L,size=(k,n))

return w

def main(): # computes synchronization time of two Tree Parity Machines

# with 2L+1 weight values, k hidden nodes, and n inputs to each

# hidden node

L = int(sys.argv[1])

k = int(sys.argv[2])

n = int(sys.argv[3])

w1 = initialize(L,k,n)

w2 = initialize(L,k,n)

(steps,useful,keys) = sync(w1,w2,L)

print "Synced in "+str(steps)+" steps, "+str(useful)+" useful."

main()Alright so "you're basically done" you might say, "just slap that python script on to the Arduinos and go collect your prizes" you tell me.

Well hold your little ponies buster, not so fast.

For one, Arduinos don't like Python so we will first need to convert this to .C and then do some cross checking with the Python code.

This wasn't too bad as far as I can remember, but I might need to check with a teammate on the veracity of that statement.

I think the headache really was in the next two steps.

After the .C conversion the code then needed to be split up in a way such that we have a master and slave device, i.e. we only want one device generating new random input vectors.

Then transitioning, where necessary, the .C code into calls and functions actually contained in the Arduino ARM libraries such that our algorithm will actually run on these little devices.

This coupled with understanding the real time serial communication, memory buffers, and just really base level computation managing was surprisingly challenging (for the time frame).

And I think I can safely say the latter step is stuff that none of us had anticipated having to deal with.

That being said it is often the most surprising things that are the most interesting, and it really was interesting having to figure all this stuff out.

However it being interesting had no real dampening effect on how frustrating it was to get it all to work.

With that we ultimately got the proof-of-concept like 90% working the night before the expo.

Now I know your thinking, "what in the flying fuck does 90% working mean?"

Well I'll let Sebastian tell you:

"I am now remembering something about the communication protocol (I2C I believe) not working exactly like we expected. I remember we spent a long time trying to send simple bit sequences and failing."

And I should probably say that I am writing this post quite a while after the event so all of our memories are a little fuzzy.

What this meant was that none of us got any sleep the night before the expo.

We were all working on this bug for what had to be at least six hours right up until it was time to set up our table at the expo.

And honestly I was pretty proud of our systematic approach of figuring out what it couldn't be.

And well by the time we had to stop working on this we were honestly all convinced that there was an issue with the Arduino ARM libraries as we had done everything we could to leave no stone unturned.

And I am pretty sure every stone was turned a number of times.

But I'll be honest we (well at least me) didn't follow up on this after the competition.

But I'm also fairly confident that if we had just used the flagship Arduino UNO with its well vetted libraries we would have never had to endure this headache.

I think the Arduino MKR1000 being some smaller more obscure microcontroller was really our problem.

So ultimately we couldn't get the full proof of concept working 100%, and this was a little crushing at the time.

But anyway we had to make due with what we had and start pitching our hack.

And what we did have working was a 'half-simulation', the nice little colorful gif shown previously, and a pretty darn good pitch.

Now you're probably wondering what a 'half-simulation' is, and well it is pretty much what is sounds like.

It is something that came out of our debugging marathon as we knew our simulated TPC worked and so we developed a mash up of the simulation laptop based code and the pure Arduino code in order to pin point where our bug was.

i.e. we had a single Arduino running the slave code hooked up to the laptop, which was running the master code, and that had always worked.

So this what was set up at the expo an were on a loop performing the super cool tree parity machine key exchange like gangbusters.

So all was not lost and we did have something pretty cool to present come judgement day.

We also had a cool logo you can see below which I made :).

Well judgement day was nigh.

The first round was a little rough at the start as we were immediately coming off of the mild failure of being so close to having our hack 100% working.

This in addition to the standard roughness of refining our individual pitches.

I think we had enough practice before the judge eventually came along though.

But even so there seemed to be some resistance to our hack, something that felt very familiar from the last hackathon we did.

It was this sense that the judges were more looking for some hack that had a clean web design instead of something that actually did something interesting.

Still not salty.

Despite this resistance we did make it to the second round (yay!).

This round differed from the first not only in it having fewer teams (obviously) but also in the number of judges that judge you (i.e. more than 1).

And it suffices to say that the resistance I mentioned earlier reared its head once more.

And unfortunately the judging pool appeared to be a bit more homogeneous this this time, i.e. no outlier that was in our corner.

And with that, despite some excellent pitching and the coolest neural net synchronization gif you've ever seen, we did not make it into the top 10 to go pitch in the final round ☹️ .

No prizes this time around and no live video feed of our final presentation.

But I did think we built something really cool.

And like they say, it's the journey, not the destination.

But I mean some prizes at the destination wouldn't have upset us.