First Hackathon: Pennapps XIV

In my very first hackathon experience our team of physics PhD students mashed together some transparent LCD hardware, a couple of webcams, and some facial recognition software to create a pretty neat piece of tech and proof of concept. We came away with a few prizes and some patent dreams.

What's a Hackathon?

Now if you are not aware, PennApps is one of many student hackathons around the world where students ranging from high school to grad school come together to 'hack' together creative software and hardware projects. Whereby these events use the Frankensteinian definition of hacking, i.e. putting together disparate technologies to make something new. At these events students work in small teams over the course of 36 hours, functioning on Soylent, coffee, and snacks (all free), in the hopes of bringing their ideas to life (and also maybe winning some cool prizes ;) )

PennApps also happens to be the biggest student hackathon in the U.S. at the time of writing. Serendipitously the competition just happens to be hosted at The University of Pennsylvania, the institution in which I am doing my PhD. Also the building that the event takes place in twice a year is right across the street from my office. The convenience of all of this was all pretty ideal for me and my other physics PhD partners. I could even walk home and sleep in my own bed instead of having to pass out on the hard ground of the engineering building like all the other attendees had to, a luxury to be sure.

For me, all of this really started with a friend and colleague of mine, Rob Fletcher. Rob really sold me on his first hackathon experience. And well you would probably be sold on it too if your first experience was his. Rob was coming off of the then most recent edition of PennApps, PennApps XV, which just happened to line up with Philly's biggest blizzard that year. Using the blizzard as an excellent excuse to stay inside and hack away for the entire competition, Rob and his team put together a pretty cool piece of tech (and even got some media attention 1, 2) and ultimately won 1st place overall at the competition.

So before this I had never even heard of this kind of event existing, let alone would have imagined that you could win cool prizes, I was eating up this great victory story. This whole hackathon thing certainly seemed like my cup of tea. And not just due to the prizes and convenience of the event, I have always enjoyed trying to think of creative ways to solve problems (often things that inconvenience me and that in my mind should be solved problems) and then trying to run through step by step how exactly I would solve this problem/build this thing. This interest probably very much coupled with me doing a PhD in physics, since most of our training is really learning how to break down problems to their base components and then systematically building a picture of a potential solution, solving things from 'first-principles' as we like to say. So after hearing Rob's victory story and how much he enjoyed the experience I was pretty jazzed and certainly on board for the next iteration of PennApps.

PennAppsXVI: The Hackening

Alright, so on to the actual event. My teammates were also all PhDs in the physics department at Penn. The idea for our project was from the then reigning champ, and now teammate, Rob. In his own words:

The beginnings of this idea came from long road trips. When driving having good visibility is very important. When driving into the sun, the sun visor never seemed to be able to actually cover the sun. When driving at night, the headlights of oncoming cars made for a few moments of dangerous low visibility. Why isn't there a better solution for these things? We decided to see if we could make one, and discovered a wide range of applications for this technology, going far beyond simply blocking light.

So we set out to develop a proof of concept to solve this problem.

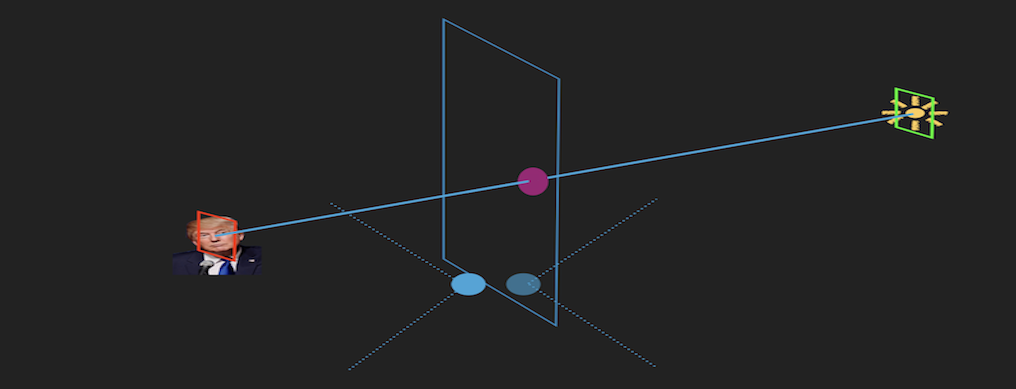

How? Well, in one dense sentence, We wanted to create a dynamic window heads up display (HUD) that could track real world objects, as well as the user simultaneously, and then have superimposed information on the display window on the objects of interest relative to the user.

The 'super-imposed information' in this proof-of-concept would simply be a black dot rendered by the HUD that would block the bright light from your eyes regardless of where your eyes, or where the light, is at any time.

A mock up we made for a presentation during competition can be seen below.

So to do this we needed a transparent LCD screen to act as our "windshield" as in the car example given above. Unfortunately these types of displays are not really readily available (or cheap) as they really only have appeared (as far as I know) as proof of concepts at CES and other such events. So instead we had to settle with a much lower budget option, your every day LCD computer display. The idea was that the monitor, when broken down to it's bare glass, was transparent enough to do what we wanted. Well luckily we did happen to have a LCD monitor with a broken backlight in our office. So there in started the tearing apart the many more layers of an LCD screen than I had thought existed. I won't go into the details, but at essentially every new layer of the monitor that we had to remove we were all convinced that the project was dead because we couldn't remove the next layer. Yet, we persevered and ultimately were able to get the bare glass out of the monitor (and still have it be working!).

Now with our 'transparent' monitor up and working, a laptop webcam to do the user tracking, and a separate webcam that we bought from a CVS that night to do the object tracking, we had essentially all the hardware we needed to try to get this hack working.

On the software side we stumbled upon the open-source facial recognition software "OpenCV." We ultimately used OpenCV's haar cascade classifier in python to perform our facial recognition. Once the facial recognition was done we needed to locate the users eyes in 'pixel space' for the user camera, and locate the light with the other camera in its own pixel space. We then wrote an algorithm that was able to translate the two separate pixel spaces into real 3D space, calculate the line that connects the object and the user, finds the intersection of this line and the monitor, and then finally translate this position into pixel space on the monitor in order to render a dot in the correct position. If you lost count that is three different pixel spaces we are working with. In order to make everything work we had to develop a calibration procedure in order to find the right transforms between these different pixel spaces. The procedure was as follows

- Pseudo-randomly place the dot on the screen such that it sampled the screen thoroughly.

- For each dot placement have the dot obstruct the light source relative to the user (move head/source around s.t. this is the case). The user and the source must maintain a set distance away from the LCD screen (i.e. in a plane) during the calibration due to the single camera limitation of our proof of concept.

- For each iteration use constraint equation for three points lying on the same line in some common space to compute the transforms.

- Fit transforms to find best fit (calibration) value.

Below are these constraint equations of three points lying on the same line in real space, taking into account the possible shifted coordinate system in each digital space plane (LCD, face camera, Sun camera).

Taking our LCD space to be the 'real space,' , the best fit values and for the face camera and sun camera are determined from the procedure described previously.

This calibration procedure that we came up with to provide the right transforms between these pixel spaces was probably what we were most proud of in the end. The next difficulty after we finally got a working proof-of-concept was getting accurate tracking on the bright light on the far side of the monitor. The web cam we were using was cheap and we had almost no access to the settings like aperture and exposure which made it so the light would easily saturate the CCD in the camera. Because the light was saturating and the camera was trying to adjust its own exposure, other lights in the room were also saturating the CCD and so even bright spots on the white walls were being tracked as well. We eventually solved this problem by reusing the radial diffuser that was on the backlight of the monitor we took apart. This made any bright spots on the walls diffused well under the threshold for tracking. Even after this we had a bit of trouble locating the exact center of the light as we were still getting a bit of glare from the light on the camera lens. We were able to solve this problem by applying a Gaussian convolution to the raw video before trying any tracking. This allowed us to accurately locate the center of the light.

Putting it All Together

By some miracle we were able to get a pretty good proof-of-concept working. It wasn't the most optimized (clunky python script that was also doing a lot of work rendering other metrics on the screen) but it worked! In the video below you can see the magic happen. Note that the dot seems to be offset from covering the light but this is just because the camera is offset from my eyeballs. There was a balancing act there where I needed to get my phone camera as close to my eyes as possible to best demonstrate the rig, and at same time needed my face not to be obstructed so that the facial recognition worked!

The Competition

In the first round of competition we were separated into two heats, as there didn't exist a large enough indoor hall at the university for every team set up at a table at the same time. We were in the first heat and had to be there bright and early at 9am. Immediately our first challenge became just transporting our delicate contraption through campus to the competition area. So after maybe three hours of sleep we loaded up the device onto a roller cart thing that we stole (borrowed) from some maintenance crew and made our way over. And believe you me that stripped down monitor screen felt every crack in the sidewalk. Nevertheless we overcame this trial and made it to the first round before start time. We did not arrive unscathed however, as upon start up of our hack it became apparent that a single column of pixels on our screen were now dead. Not a huge loss but something to be mindful of.

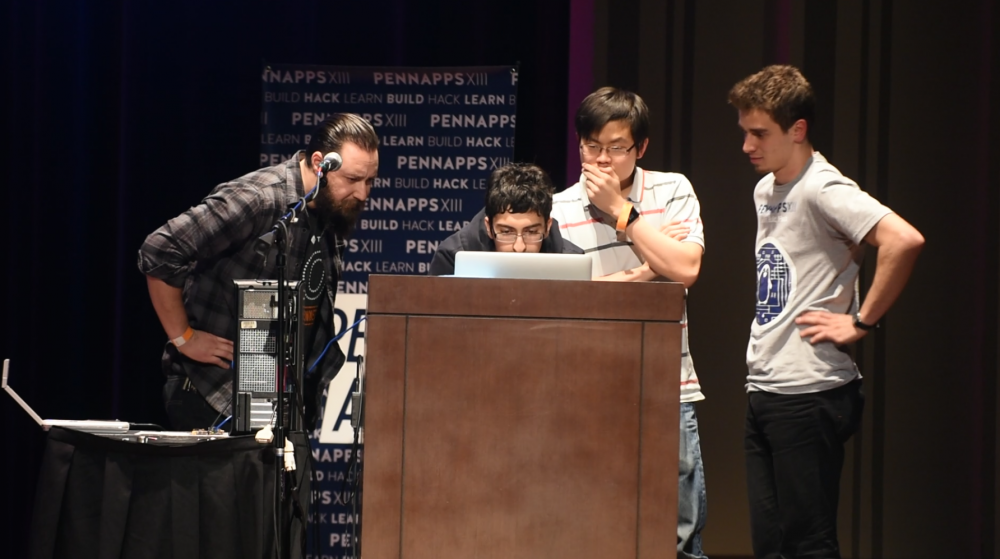

The expo began and we began pitching our project hard in the competition hall. In the above photo you'll find the team and our set up at the second table up from the bottom right. You can see me in the grey shirt and khaki shorts (facing the camera) giving our pitch to a man in bright orange pants and a teal shirt. We all felt that the whole first round of this expo thing went really well. It was hard for us to survey the popularity of other hacks at the expo purely because we were all busy running our hack and pitching to a constant stream of people. But maybe this was a good problem to have. The next step was to simply wait for the results from the judges on which teams made it to the second round. Our team name was ultimately announced and we were still in the running! Now unfortunately I wasn't able to source any photos from this round but it was in an entirely different hall that was up two floors from the expo hall. So naturally we lost a few more columns of pixels with this move. This round also went pretty well but the judges were definitely more critical with their questions, which I think we all fielded pretty well. We ultimately only really had one judge in our corner who could really understand the potential applications of something like this, as well as just how difficult it was to throw this together in 48 hours. As the second round came to an end we again waited to see if we made it into the next round which would be the final round made up of the top 10 teams of the hackathon. In this round each team is to present their hack on stage in front of all the hackathon participants as well as be live streamed. Well, spoilers: we made it! On to another building to break more pixels in our monitor! Continuing with the drama we had to go last due to our relatively complicated setup. In the picture below you can see our team up on stage doing our demo bit.

We have Rob acting as the viewer, Sebastian moving the flashlight around, Dillon giving the pitch, and me with my hands on my hips staring at the big screen. The pitch went well, the only hitch being something I mentioned previously with respect to the video demo (and can be more easily seen in the header image at the beginning of this post), which is unless you are the user sitting in the chair, and having your face being tracked, you really can't see how well it actually works. But the hope was that, with some explanation in the pitch, the audience would be able to interpolate well enough what was happening. With the demos being over we now waited to be judged, with prizes only being awarded to the top 3 of the 10 teams in the final. We were hopeful as we had a lot of interest from the public through out the whole competition, and the level of difficulty of our hack was relatively high. However we really only felt we had one judge (out of 4) in on our side, so it was really up to him now to make our case for us. Below we have the video of us pitching our hack in the final round. After our pitch you can skip ahead to the results at 1:37:17.

So if you skipped the video well I don't really know how to build suspense in written text (as you've probably noticed) so I'll just cut to the chase here. We came in 3rd! Yay! With that we had a choice of prizes but all ended up deciding on an Oculus rift. The fact that our tracking display worked at all we felt was a huge accomplishment. Every stage of this project felt like a big victory. After a couple of mostly sleepless nights and constant battling with endless new problems it really was quite satisfying to come away with a cool hack and some swag.